Will sustainable aviation take off in time?

Over the past few years, we’ve seen some considerable changes in transportation, and conceptual ideas are coming to life as a result of great electric propulsion triumphs. It began with the transition from fuel to electric, and now air travel is taking a turn to incorporate further means of mobility.

Historically, the bigger the engine the more power and thrust an aircraft has, determining its suitability for short and long-haul flights. As it stands, you would fly light aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean; likewise an Airbus A380 is unsustainable as an intercity transport mechanism.

Similar principles apply in a sustainable aviation space with organisations looking at new ways to make aircraft that are suitable for specific tasks, and more flexible depending on the application. The ratio of weight to power is the current battle that technicians are facing in every instance, but battery architecture enables a different use of the skies above us. Electrical systems drive aircraft decarbonisation, which in turn is opening up new and intuitive ways to travel.

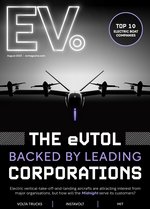

eVTOL could be a national aviation solution

Take the electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft as an example. With minimal components required by an all-electric system, aircraft engineers are stepping away from a conventional design to utilise a drone-style propeller layout, by creating aircraft that fits into the current culture of flexibility and convenience. However, this isn’t without its challenges.

“Vertical take-off aircraft demand a lot of power, and that's been one of the issues that's limited their wider deployment in the past. With distributed electric propulsion you win on multiple accounts,” says Jia Xu, CTO, Honeywell UAM and UAS.

“There's the noise benefit, there's a safety benefit, uh, but now you can also operate in this vertical takeoff mode without as much penalty as you had historically.”

The innovation we see in eVTOLs is testament to the capabilities of all-electric systems. Electrical components alleviate the need for more space to encapsulate bulky engines and fossil-fuel-driven propulsion systems. This principle is seen in the automotive industry as well with more vehicle manufacturers paying attention to the internal user experience and maximising smaller craft for larger capacity.

Then there’s the propulsion layout. Traditionally, aircraft were built with large engines or propellers to provide the maximum power from one or two eternally mounted pieces. eVTOL enables a new, comfortable, and sophisticated means of people and parcel transport. They are given near car-like agility in the sky, which could create a flexible approach to aviation—something of a sci-fi movie prediction.

The idea of eVTOL on a wider scale is more than a novelty, but an exercise that could reduce aviation costs and enable purpose-built aircraft that are scalable.

“Rather than having a giant electric motor, it can have 12 little ones—without paying too much penalty. Essentially the fixed cost of each motor is quite minimal. That allows you to create this distributed propulsion arrangement where you can gain the safety benefit and the control benefit,” says Xu.

“Scalability also comes into the vertical takeoff dimension as well. That just means if you make a small, let's say five kilowatt electric motor, pound by pound—or kilogramme by kilogramme—it scales very well when you go to a 200 kilogram motor.”

Can electric decarbonisation international flight paths?

These are all well and good from a national perspective, but what about international transportation?

With more than 38 million international flights taking place in 2019—decreasing rapidly by around 16.7 million due to the coronavirus pandemic—aviation plays a significant role in economic success, commerce, and recreation. But, the level of pollution that sparked change among airline operators to adopt more sustainable solutions.

Present efforts are focused on creating hybrid aircraft models or adopting SAF to reduce emissions by as much as 80% for trips abroad, but questions abound whether all-electric would be a suitable solution for long-term industry use.

“There's going to be a crossover point, whereby if you fly longer and longer ranges, you're going to need hybrid power to match the energy density of the fossil fuels,” says Xu.

“There are alternatives. You can use a hydrogen fuel-cell system, which would be the same kind of backend prime mover, providing that sustained high energy density for the electric motor at the front. But, more than likely, with that hybrid system, you're still going to need electric motors at the front.

“You're probably going to need batteries to give you that high response time power, and then you're going to have a generator—be it a fuel cell system or a turbo generator or an internal combustion engine—to provide you with that sustaining element of power.”

When you consider all of the components Xu mentions, not only does it begin to sound expensive, but also very complex and heavy. It seems that solutions are enabling extended flight for hybrid-powered aircraft, but the inevitable truth is that they still burn fossil fuels—they don’t produce zero emissions.

This is the problem area that technicians are looking to resolve, because larger passenger aircraft are currently operating on a hybrid basis, but the goal is to get to zero emissions. So, how will they do that?

By slowly increasing the capabilities of electric propulsion in commercial aircraft, and perhaps hydrogen will make its way into the mix as its widespread use is yet to be leveraged fully.